In Search of the Andean Condor

In Search of the Andean Condor

The Andean condor is the largest bird of prey in the world and, as its name suggests, is synonymous with the Andes mountains in South America. This special bird holds a central place in the region’s culture, religion and identity. The Andean people have depicted the Andean condor in their art and music for over 4000 years, and the bird frequently appears on stamps and banknotes in Andean countries.

The condor lives in the highest and wildest places in the Andes, away from human interference. Despite its massive size, it soars effortlessly across the mountains in search of the carcases of dead animals like llamas.

When I found myself in Cusco on my way to visit Machu Picchu, I had to see this mythical creature. A bit of research told me that there was a viewpoint at a place called Chonta, a couple of hours’ drive from Cusco. The Chonta Mirador de Cóndores or condor viewpoint is a legendary spot for viewing these birds as they ride the thermals over the majestic Colca canyon, the second deepest on the planet.

Given the altitude and terrain, I knew I’d need a guide and researched local experts before leaving the UK. This proved difficult. There were plenty of general tours which had brief condor stops as part of a wider day trip, but few specific ones.

Eventually, I found Peru Unique Destinations and selected their Condors of Cusco tour. They were extremely helpful and flexible. When I booked, my wife, Carol, had a leg problem and couldn’t manage the 5 mile round walk to the viewing platform. They offered to supply a pony so she could still come along. Fortunately, her injury cleared up, so it wasn’t necessary.

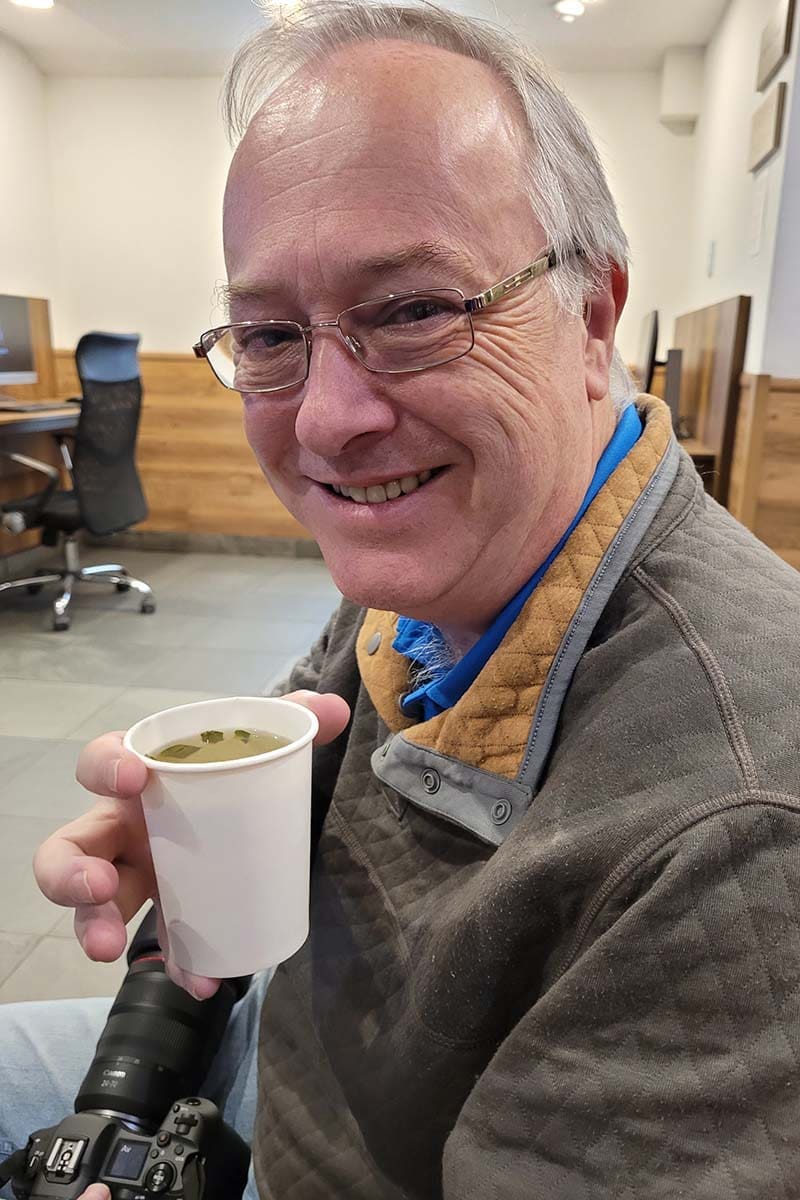

After an early breakfast at our hotel, Hotel Conquistador, in the historic centre of Cusco, we met our guide in reception. Cusco is over 11,000 feet above sea level, so altitude sickness is a genuine concern for visitors. With centuries of experience, the locals have developed a remedy to help stave off the effects of altitude sickness. They make a tea from the leaves of the coca plant (yes, that one) to help oxygenate the blood. Most hotels have a bowl of leaves and a hot water urn in reception to allow guests to make coca tea. Ours also had a giant oxygen cylinder just to reinforce the point.

Our first destination was Limatambo, a small town just under two hours from Cusco. We stopped for a coffee and to pick up a picnic lunch before the proper business of the day started. Apart from the condors, which were obviously the headline act, we were hoping to search the mountain road for some regional endemics.

Shortly after the town, Raul turned off the highway onto a twisting single lane road which took us higher. Alexander had his binoculars in one hand, and a big bag of coca leaves in the other. He and Raoul were picking them out of the bag and chewing them like they were crisps. Obviously, the coca leaf thing wasn’t just for the benefits of tourists.

The winding road snaked upwards, offering us superb views. Every so often, Alexander would call a halt and we’d pile out to bird a section of road. One flowering tree yielded a few hummingbirds, including BLACK-TAILED TRAINBEARERS and GREEN-TAILED TRAINBEARERS, GIANT HUMMINGBIRD, and cracking views of the endemic, GREEN-AND-WHITE HUMMINGBIRD.

We stopped frequently, walking for a bit, then driving higher. The views were spectacular and birds like BAND-TAILED SEEDEATER, GOLDEN-TAILED SALTATOR and another localised endemic CREAMY-CRESTED SPINETAIL showed well, as did an Andean Fox. Mid-afternoon is the best time to view the Andean condor, so we weren’t in too much of a rush.

Finally, we arrived at the community of Chonta. The landscape now was arid and rocky, with low scrub and the occasional sparse tree. Before setting out for the viewpoint, we had a quick lunch at a picnic table watching a pair of ANDEAN FLICKERS against the backdrop of towering snow-capped peaks.

The walk to the viewpoint was around 2.5 miles along a winding mountain path cut into the steep slopes of the canyon. On a short uphill section, I spotted another lifer, BLACK-BILLED SHRIKE TYRANT hunting the rocky terrain to our right. Slowly, the path levelled out and was relatively easy, despite the altitude.

We continued to find new species as we moved along the track. ANDEAN SWIFTS buzzed us in numbers and a family of SMOOTH-BILLED ANI fussed around on some bare branches. A little later, a beautiful RED-CRESTED COTINGA showed nicely, perched in a bush down the slope from us.

A few hundred yards further on, Alexander pointed to the first viewpoint. There are 3 Andean condor viewpoints along the trail. It’s possible to get lucky at the first, but viewpoints 2 and 3 are the most likely to yield the best views of the condor. We stopped for a quick scan of the valley, but saw nothing, and Alexander led us onwards. The second viewpoint is located at trail level and set back from the canyon. It has a straw roof to provide some shade for viewers and avoids the scramble down to the main viewpoint (which Carol was happy with.)

I needed better views to get good photographs, so we set off down what was little more than a sheep (or llama) track. Luckily, it zig-zagged its way down to the concrete platform as there was little more than a single, shin high wire between us and a thousand-foot drop.

As Alexander set up his scope to scan the canyon walls for perched Andean condors, we heard a commotion above us. A class of 8-year-old schoolchildren with their teachers descended noisily to the platform. My first thought was that the teachers were incredibly brave, bringing young kids here given how exposed the platform was. No way would a British school party be allowed anywhere near this place.

Soon, the teachers were on the very edge of the platform on the wrong side of the flimsy wire, mobiles out, taking selfies with a death guaranteeing drop below them. No wonder the kids were comfortable.

Alexander called me over. He’d found some condors sitting on nests in shallow caves on the canyon wall. The chicks take a full 6 months to fledge, so they generate a lot of guano, which helps in spotting them against the dark rocks.

There wasn’t a lot of flight action, so we settled down in the afternoon sun to wait. The kids had fun practicing their English with me, and looking through Alexander’s scope, but soon got bored.

Eventually, we had a few birds soaring below us (strange concept, but the canyon really is that deep). We still hadn’t had any point-blank views and were starting to despair. We were ready to give up, when Alexander shouted and pointed. A condor flew over the top of us from behind. The size of these birds has to be seen to be believed, they are massive and to have one so close was a real treat.

Display over, it was time to head back to the trail. It was at this stage I realised my mistake. The downhill scramble was now a steep uphill slog. I walk a lot, regularly doing 8 miles or more, but it turns out walking in flat, sea level Essex doesn’t prepare you for the Andes. A quarter of a mile at 11,000 feet is a very different proposition to a stroll along Southend seafront. Add binoculars, a backpack and a heavy camera with a long lens, and it’s a recipe for disaster.

I wasn’t a quarter of the way up before I started having breathing problems. Half way up, I was bent double and wondering if they had an air ambulance in Peru. I genuinely thought I was in serious trouble. Alexander, who had prior experience of dealing with idiot tourists, took my gear off me, and sat me down to recover.

The rest of the trip back to the top was still a struggle with a lot of stops to regain my breath, but I eventually made it. In the meantime, the kids skipped up the track like mountain goats. Back at the second viewpoint, Carol rubbed salt in the wound by describing the point-blank views she’d had of the flyover condor, which had come right over her viewpoint.

After a brief recovery stop and some water, we headed back to the bus. The walk back wasn’t too bad, it was mainly level with no particularly steep bits, so I was fine. Ahead of us, we could hear the voices of the kids as they raced back to the village. We thought they’d be long gone when we ambled back down the slope to the car park, but they were still in the picnic area. They’d arrived to find their minibus had a flat. Raoul helped their driver change the tyre while we chatted and swapped emails with the teachers as they wanted copies of my photos.

This delay meant a late departure back to Cusco, but it didn’t matter because when darkness fell, the most spectacular starry sky revealed itself. A perfect end to a great day.

Related Articles

No posts found.